Continued from Part One

[Part One is a story of magic. I struggled to flesh out the story of this second part, experiencing long periods of writers’ block, because I desperately wanted to continue that sense of magic I felt in my experiences described in Part One. But the story of Part Two that was there to be told has a different flavor. It’s more of a palpable encounter with history, largely the tragic side of it, rather than another palpable encounter with magic (though in my experience, there’s magic even in the seemingly mundane, it just sometimes lays hidden from our senses). When I accepted this, I was finally able to write and complete this post. Here it is, delayed, but in its realness fraught with darkness, and also rays of light shining through the cracks.]

I arrived in Glubokoe, the Belarusian (formerly Lithuanian) town my great-grandfather Yakov Meytus was from in the afternoon on the Wednesday before Yom Kippur.

Kostya picked me up the next morning from the hostel I had set up in. I thought we were simply going to meet up for tea and that he and his wife Anya would show me on the map where all the sites of Jewish heritage they knew about were. But they had other plans. Kostya proposed that he would actually give me a tour of the Jewish heritage sites first and then I would come over to their place for lunch. Anya was at home already preparing the lunch. I was much obliged.

The first place he took me to was the Holocaust mass grave site. It was in the forest on the edge of town. That was where the Nazis took the Jews the first couple of times (there were actually two mass graves next to each other) they liquidated the Glubokoe ghetto. The Nazis ordered the Jews to dig a massive pit before they shot them all into it. We stood there gazing in silence. The weather was cold, grey, and dreary; apropos for the place we were at and the history we were there bearing witness to.

Kostya eventually broke the silence, commenting that it’s weird and sad that this is how they introduce their guests to the town. He said he wished that instead he could show me a Jewish festival or dance or Yiddish theater, but unfortunately this is the reality: those are gone and these mass graves are most of what’s left.

It’s a sad reality for so much of Eastern Europe. Almost everywhere I’ve been, there are mass graves of the Holocaust. I hadn’t realized when I began this journey how prevalent they are. In the Holocaust education I received back in the states, the focus was mostly on the concentration camps and death camps. We didn’t talk much about the Nazi mobile killing units (often aided by local collaborators) who perpetrated a significant portion of the mass murders of the Holocaust, across German-occupied Soviet territory. Estimates are that some two million Jews were shot to death in the German-occupied Soviet Union. Eastern Europe is dotted with thousands of mass graves from these Holocaust mass killings. I hadn’t realized at the beginning of my journey, that almost every village, town, and city I would visit in Eastern Europe would have one. Sometimes more than one.

In virtually every town I’ve been in, the locals who end up guiding me go out of their way to show me the mass grave sites. They usually don’t even ask if I want to go there. It’s not a question for them. It’s very much alive in their consciousness. They live next to these sites. Not all the locals are always aware of it. In many parts of Eastern Europe, these sites were only marked and remembered in recent years, since the collapse of the Soviet Union (where the tragic history of the Jews was swept under the rug). It seems to me that they were like wounds festering, and in many places in Eastern Europe, the healing of these wounds has only recently begun. Those who are aware of these sites seem to have a need to show visitors, to have outsiders, especially those with a connection to their land, bear witness to the history they live with everyday.

Despite having already borne witness to many of these sites throughout my travels, the initial shock of stepping foot next to a place of such tragedy, trauma, and grief still hits me. There are often are no words in those moments. Just silence and tears. Silence in which the wind, the crows, grey skies, and the aura of untimely death saturated into the Earth ring loudly all around.

Kostya and I each grabbed a stone from nearby and laid them on the memorial to let the dead know that we honor them. I softly sang the prayer for the souls of the departed, El Malei Rachamim.

Kostya led me to another memorial nearby. This had one had a cross. It was a memorial to the local Righteous Among the Nations, dozens of non-Jews from the town who gave their lives in an attempt to hide and save the lives of their Jewish neighbors. Unfortunately for those in this mass grave, there was no one to hide them once the Nazis discovered their subversion.

After we were back in his car, I asked Kostya if he knows where the old synagogue was. He said he knows the general location, in the center of the town, but that he knows someone who can tell us the exact location. He called up a woman who is a friend of a friend, a local historian named Alla. Before I knew it, we picked up Alla at her house as she offered to give us her expert guidance through the old shtetl, providing, according to Kostya, more information than Kostya was able to on his own.

Our first stop with Alla was another Holocaust site. We came to the site of the former ghetto, where the Jewish population of Glubokoe along with Jews from surrounding villages were rounded up and crammed. Now it’s a park surrounded by residential homes, with a memorial to the victims at the edge of the park. Alla explained that there were a few liquidations of the ghetto, when those deemed unfit for work were taken to the forest, at the site of the mass graves where Kostya and I were before, and shot.

The final liquidation of the ghetto came when Soviet partisans were attacking targets near Glubokoe. The Nazis feared the partisans would make contact with the ghetto, so they prepared to deport the remaining Jews. When the Nazis entered the ghetto, they were met with armed resistance. Through the help of resisters on the outside, arms were smuggled into the ghetto. Groups of Jews organized and prepared themselves in anticipation of the final liquidation of the ghetto. Fighters were in the minority among the ghetto prisoners, but they put up enough of a fight to kill dozens of Nazis. The Nazis, having failed in their plans to deport the Jews to a death camp, systematically set fire to the ghetto. 4,500 died in the flames, or in a barrage of bullets and grenades when they fled the flames. A few dozen managed to escape through the hell-fire and they joined the partisan groups in the forests not far away.

We stood there next to the monument on the ground where those thousands were lost to the flames. Again the silence we stood in was deafening. It’s one thing to read about such horrific events. It’s another thing to stand on the grounds where they occurred. The tragedy becomes palpable. It touches another level of consciousness that reading or hearing stories doesn’t quite reach. Face-to-face with history, the reality of it sinks in deeper.

This time, Alla broke the silence. Alla asked me if I had any relatives there during the war. I told her I don’t know.

My great-grandfather Yakov moved from Glubokoe to Odessa well before the war, even before the Russian Revolution. While digging through the archives, in Odessa and in Vilnius, I found that it was actually Yakov’s father, Gersh, who moved to Odessa, along with his wife Maria and all the kids (five in total). I also found, through the Lithuanian archives, that they left behind some relatives. Quite a number of relatives. I’m not sure what happened to those relatives; whether they stayed behind or moved from Glubokoe at some point before the war. I’ve only been able to find one Meytes from Glubokoe in the Yad Vashem records, and I haven’t been able to trace whether or not they were a relative. But it’s very possible, if not probable, that they were. Alla expressed her opinion that more than likely they were. Glubokoe was another shtetl where people did not usually share last names by mere coincidence.

It’s very possible that some relatives had been in that ghetto and in those mass graves. I wondered if any relatives were among the few who miraculously made it out and joined with the partisans. I wanted to believe that if my relatives were there, they were among those who made it out. I knew the chances were very slim though.

Our next stop was the old Jewish cemetery of Glubokoe. This was one of the oldest cemeteries I had come across thus far in my journey. The cemetery dates back to the fifteenth century, attesting to the centuries of Jewish presence in that old shtetl. To say Jewish “presence” is to put it lightly. According to the 1897 census, there were 3,917 Jews living in Glubokoe, comprising 70% of the total population. It wasn’t simply a town with a Jewish quarter. It was a Jewish town.

Thousands had been buried at the centuries old cemetery. It was desecrated by the Nazis, and most of the tombstones are gone, probably used to pave a road somewhere in or near the town, as such was the common case under Nazi (and then Soviet) occupation.

Alla pointed out that the cemetery was on land with the best view in the town, overlooking one of the central lakes. It was quite picturesque. One thing I’ve noticed on my travels is that we Eastern European Jews liked to give the ancestors a great view at their final resting places.

Alla was limited on time, so we had to move on without going into the cemetery. But I intended to come back later on my own. My ancestors were buried in the ground somewhere there.

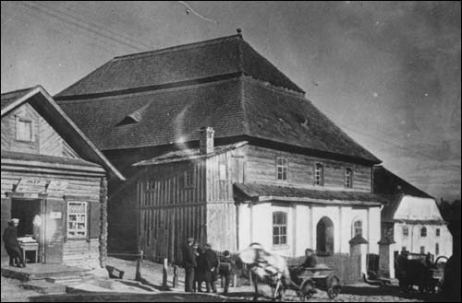

Next we drove to the center of town. We came upon the main hotel, named after the town. We got out of the car. Alla pointed to the hotel, and explained that this was where the central synagogue of Glubokoe use to be. The Nazis burned it to the ground. Some years after the war, the hotel was built in its drab, Soviet-style architecture, common throughout this central part of town, over the charred ground where the synagogue once stood.

I walked over to the front of the hotel, and pictured the crowds gathered in front before and after services. I imagined my many Meytus ancestors coming here for the annual sacred day that was once again coming up soon. I wondered how they prepared for the fast. Did all the Meytus families gather together in someone’s home before heading to this house of prayer? How did they approach the day? Did they observe it just because tradition said to, or did they engage with it as an opportunity to cleanse and purify their souls, to empty themselves and create space for connection with the divine?

I touched the ground that held their prayer house, that supported their rituals and prayers, said “hello,” and offered my gratitude.

Alla then took us by the lake in the center of town. Now surrounded by parks, churches, factories, and a couple cafes, the lake use to be the center of a mosaic of Jewish families, with Jewish homes all around. While there was a mikvah next to the old synagogue, it’s likely that in the summers, the lake was also used for sacred ritual immersion purposes.

Our final destination was a square at the intersection of the two main streets in town. On the square stands a row of statues of famous historical figures from Glubokoe. Most were Belarusian, but in the center we came to the statue of one famous Jew who lived a portion of his life in Glubokoe: Eliezer Ben-Yehuda, widely regarded as the father of modern Hebrew. Born in another Belarusian (formerly Lithuanian) village, Luzhky, about thirty kilometers north of Glubokoe, Eliezer Ben-Yehuda’s parents sent him at a young age to yeshiva in Glubokoe. This was during the time my Meytus ancestors were in Glubokoe. Perhaps my great-great-grandfather Gersh Meytus (Yakov’s father) was in that same yeshiva with Eliezer Ben-Yehuda. Or perhaps they knew each other from synagogue or run-ins at the market. Did they have conversations together I wonder? Did Ben-Yehuda ever mention his spark of interest in reviving Hebrew as a spoken language?

Our final destination was a square at the intersection of the two main streets in town. On the square stands a row of statues of famous historical figures from Glubokoe. Most were Belarusian, but in the center we came to the statue of one famous Jew who lived a portion of his life in Glubokoe: Eliezer Ben-Yehuda, widely regarded as the father of modern Hebrew. Born in another Belarusian (formerly Lithuanian) village, Luzhky, about thirty kilometers north of Glubokoe, Eliezer Ben-Yehuda’s parents sent him at a young age to yeshiva in Glubokoe. This was during the time my Meytus ancestors were in Glubokoe. Perhaps my great-great-grandfather Gersh Meytus (Yakov’s father) was in that same yeshiva with Eliezer Ben-Yehuda. Or perhaps they knew each other from synagogue or run-ins at the market. Did they have conversations together I wonder? Did Ben-Yehuda ever mention his spark of interest in reviving Hebrew as a spoken language?

We took Alla back to her home. Kostya and I both expressed our deep gratitude for her guidance through the Jewish history of the town. My heart sent out gratitude to the ancestors for their guidance as well. Alla was another connection I wouldn’t have made without that run-in with Gidaliya back in Vilnius.

After parting ways with Alla, Kostya and I headed to his place for the lunch Anya was preparing. In the car, Kostya commented on how much he respected and appreciated that I came here with this intention to find my roots. He said that he learned some things, through our excursion with Alla, about the Jewish history in his hometown that he never knew before. Further, it intrigued him to learn more about his own roots (his family came to Glubokoe after the war from elsewhere in the Soviet Union).

He expressed that his family never embraced their Jewish roots (Kostya’s mother is Jewish and his father is Russian). They hid that side from the outside world, and he still does for the most part. He explained that in the Soviet Union, being Jewish was something that society trained them to be ashamed of, to be afraid of showing, to be afraid of being. I thought of my own family’s stories and those of so many other Soviet Jewish immigrants and the Jews I met during my travels who still live in the former Soviet Union states. I thought of my own inherited fears, which throughout much of my life, until several years ago, I was largely unconscious of and hadn’t worked through. I told him I understand what he is talking about.

When we got to his place, there was a traditional Belarusian-style feast, including wild mushroom soup (it was mushroom hunting season) and draniki (fried potato pancakes strikingly similar to latkes – evidence of cross pollination of cultures that lived with each other for centuries) waiting for us. Anya greeted us warmly. She inquired into our excursion and we gave her the overview. Of course she and Kostya asked for and so I delivered stories of my travels. When I got to my time in Vilnius, I asked if Gidaliya had told them how he and I met. He hadn’t. I relayed the story. They laughed in joy and wonder at the synchronicity.

Kostya raised a toast to our unlikely meeting. He added: years from now, after I have integrated all the strength that this ancestral roots journey is giving me and I return to these lands to show my descendants where they come from, may we find ourselves gathered once again around this table with our expanded families. My heart welled up with the prayer: may it be so.

The next day, I went out on my own to explore the old shtetl and walk the streets my ancestors walked over a century ago. Through dirt village roads lined with old wooden cottage-style houses, each with its own garden of vegetables, fruit trees, and the occasional livestock, I ventured. There was a bustling market in the center of town. I imagined it didn’t look so different in my ancestors’ time. Just the people looked different.

I eventually made my way back to my ancestors’ final resting places. I arrived to find the gate to the old Jewish cemetery locked. I asked a neighbor living across from the cemetery if they knew who had the key. They said that there is a care-taker, but that he doesn’t live in this neighborhood, and they’re not sure where he does live. They suggested I go to the town council office and ask them.

I realized that by the time I would get there and potentially coordinate to have the gate unlocked, it would be dark. The following day I was leaving Glubokoe and going with Kostya and Anya to Minsk for Yom Kippur services. This was my chance to visit the grounds. I felt conflicted. The last thing I wanted to do was to disrespect sacred grounds. Would jumping over the locked gate constitute that?

I meditated on this question for a moment. I asked my ancestors if they would feel disrespected if I jumped over the locked gate or if they would be disrespected by me not stepping foot on the grounds where they were laid to rest.

The question of how Belarusian police might react if they happen to drive by and see me in the locked cemetery also crossed my mind. Then I remembered the meaning of my name: Daniel (Daniyyel from Biblical Hebrew). It means “God is my judge.” That was the answer to my quandry.

My purpose there transcended any human-made trespassing laws. My blood was my key. The grounds were sacred to me. I couldn’t trespass there because it would be impossible for me trespass on my own ancestors’ sacred burial grounds.

I hopped the fence and was in the six centuries-old cemetery. It was relatively barren of the headstones that once crowded it. But some remained, damaged and broken, or half sunken into the earth.

All were in Hebrew or Yiddish. So I couldn’t make out the meaning of the words that were still legible on them, but I had an idea of the Hebrew spelling of my ancestors’ surname, Meytus, and began scanning for it in the off chance that they were among the few headstones that were spared.

But without knowing the meaning of the words, I never knew if the writing on the part of the headstone that remained intact included the name or if the name had been broken off. I could have been looking at my ancestors’ tombstones without knowing it. This gave each stone significance for me. It gave each tree, each blade of grass, each mushroom on the grounds, the life that was fed by the soil there, in part made up of the decomposed bodies of my ancestors, another level of significance. I didn’t know the exact spot my ancestors were laid to rest, so the whole cemetery and everything on it became their plot for me.

I made my way to the center, where a stone foundation of the Star of David surrounded what looked to be some of the oldest tombstones on the grounds. I wondered if this was where the first burials were made. This became the altar to my ancestors. I delivered the cookies and fruits I brought for them. I tapped into the praise and prayers in my heart and spoke and sang them for all who were listening.

I gave thanks for the unseen guidance that brought me to those who helped me get to know this place my roots are from, even with it’s tragic history. I gave thanks for the unlikely meeting that gave both myself and Kostya some insights into this land that gathered us together. I gave thanks for new connections in my ancestors’ old shtetl.

The next day, we (the unlikely trio) ventured down to Minsk together, the nearest place with an active synagogue, to take part in the sacred ritual of Yom Kippur our ancestors have practiced and passed down for thousands of years, generation after generation. Through successive wars, successive displacements and diasporas, forced assimilations, pogroms, and the Holocaust that so ravaged the shtetl my Meytus ancestors made their home for generations, they kept the ancient traditions alive so that we, their descendants, could remember and return to our sacred connection with the divine.

Occasionally, they put in a little extra work even after they’ve left their bodies, and send a seemingly random person to recruit us for a seemingly random minyan that we resist joining, but which ends up being exactly the right place we need to be to find the connections that help us know where we come from.

Thank You Danny! Your courage and perseverance to continue this journey is inspiring!! Your words are heartfelt, poetic and soulful. I am grateful that through your words, pictures and prayers, I get to be there with you just a little bit.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thank you Michael! Thank you for coming along with me through these stories. Miss you my friend!

LikeLike

thank you for this history, very touching. prayers that as you continue in your search you are further blessed

LikeLike

Thank you Savta!

LikeLike

Daniel, you are wrong. There is plenty of magic in this story, and you have told it just perfectly. I am so moved—I feel once again like I was with you, and I don’t even know you. One thing worries me—what happens when people like Alla and Kostya are gone? Will there be people, markers, something to keep alive the Jewish history of places like this? Who will be there to tell people like you where the shul once stood?

LikeLike

Amy, thank you for your words of support and encouragement! And very good questions! Getting markers in place would be a wonderful thing. Not just for people like me, but so that the locals know the history of the place they live and who the historical inhabitants were. I’m not sure descendants in foreign countries alone can do this, but perhaps with the weight of public figures like Eliyezer Ben Yehuda’s grandson, it would be possible. But my sense is the initiative also has to be driven by locals.

LikeLike

Yes, probably true. There should be something like the Stolpersteine project that marks not only where Jews lived, but synagogues and other places of importance to the former Jewish communities.

LikeLike

It’s an honor to make this journey with you. Holy ground indeed! Jane

LikeLike

Thank you Jane!

LikeLike

Perhaps you did not feel a palpable sense of magic during these times of your journey, but I felt magic in reading your words. Everything is imbued with magic to me when we bridge worlds and come within breathing distance to our ancestors. Thank you for pushing through the writer’s block and sharing anyway. It is always such a gift to read.

LikeLike

Thank you Tasya! Yes, I felt the magic. What I meant to say is that I struggled with conveying that sense of magic in the second part. It was easy in the first part; it was the story. At least this was my experience of the writing process. But based on the feedback I’ve gotten, it seems I did convey the magic in the second part as well.

LikeLike

Danny, I really enjoyed this post, though the word enjoyed doesn’t seem like it is really the right word. I had quite similar experiences when I went back to Lithuania in 2010 and took a side trip to Belarus to see where my mother had lived (Vidzy). Our experiences were similar, visiting Holocaust sites, cemeteries, and trying to imagine what the towns were like when we would have known everyone we passed. I actually found my mother’s house. It was padlocked shut and I still wish I would have tried to go inside. But, I didn’t have the bravery to jump that fence! I will now read your Part One, which I had not seen before. Again, thank you for posting.

LikeLike

Thank you Marlene! Wow, what a blessing that you found your mother’s house! I ended up finding out the name of the street my ancestors lived on in Glubokoe, though not the address, but only after I had already left Gives me all the more reason to go back.

Gives me all the more reason to go back.

LikeLike

Thanks Danny. Always enjoy your dispatches.

One story handed down — connected to Minsk — to me via my Siberian Jewish grandmother is about her great-grandfather, Joseph Sadovitch, who got into trouble with a policeman in Minsk and was exiled to Siberia. He left his family behind in the 1830s and started a new life in Chita, Russia. Generations later, my grandmother and the rest of her family emigrated (the Bolshevik revolution forced them out) to the USA.

I’m hoping to travel to Europe next summer and wondering if you will still be over there or plan to be back in the States by then.

Hugs to you my brother. May your prayers in the old country contain within them the prayers of all of us who know you and mourn our own ancestors who lived, suffered and either died there or endured and left.

LikeLike

Thank you Tom!

Chita is not far from where I began my travels, around Lake Baikal, over a year ago. Any plans to go there? Or to Minsk when you come to Europe?

I plan to be back in the states by summer.

Hugs to you!

LikeLike

Pingback: Journey Blog Reboot and Roundup | Journey to the Lands of the Ancestors